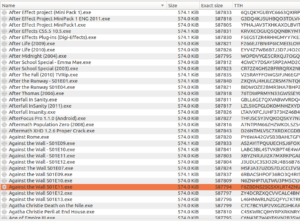

Continuing from last post… This is my first time disassembling a sample this big, so I’m going to do my best to explain things in a way that makes sense. It’ll be an interesting exercise to figure out how to keep track of such a large disassembly as I go along.

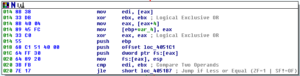

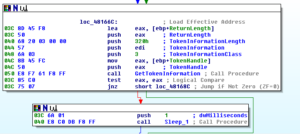

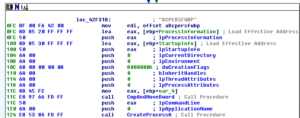

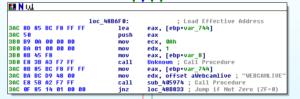

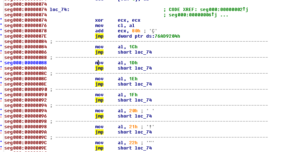

The start function is located at 48F888 and one of the first things that happens here is 0x30 is MOVed into ECX (768 decimal) and this is used for a loop that consists of pushing 0 onto the stack twice (so, at the end of this loop, you’ll have 1,536 zeroes pushed onto the stack). After this, there’s a parameter pushed onto the stack, located at 48E3C0 (which points to 0xA1) and then a call is made to a subroutine at 4076D4. This sub moves the TlsIndex then pushes a module name onto the stack before getting a handle to that module. Within this sub is another subroutine at 4051DC. In this subroutine, we see a couple of double words being set up to point to RaiseException (495014) and RtlUnwind (495018), and then a call to another subroutine at 4050C8 which directs some activity towards FS:

I think this will be a lot easier to discern when being debugged. I’m curious what offset this takes at runtime. What’s also happening here is that you can see the pointer at EAX+4 being set to the location 405028, which contains some code related to calling an unhandled exception filter.

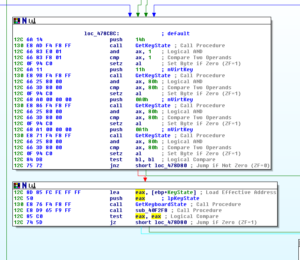

The next call after these branches is to 405174, where the code starts to get busier. A bunch of things are pushed onto the stack, and then we see that the double word at 4977D0 (which we saw had something put into it earlier, during the execution of subroutine 4051DC) is put into EAX and then this is TESTed. If the contents of dword_4977D0 is equal to 0, then we jump to the end of this subroutine and we return. Otherwise, execution continues and we hit the first block of code of 405174:

We have the contents of the area pointed to at EAX being MOVed into EDI, then we can see that the target of the pointer at EAX+4 (which, currently points to that little block of code having to do with structured exception handling) is put into EAX. This then gets put into the target of var_4 and then EAX gets cleared out. We see something located at 4051C1 get pushed onto the stack – this turns out to be a single instruction, JMP sub_404B30, which contains exception handling information:

Not to go too far down this rabbit hole, there are some interesting things in this sub 404B30. One interesting thing is one branch where a subroutine at 40450C is called:

I’ve seen other examples of using “f-” instructions as part of some sort of shellcode techniques – I’m not too familiar with these instructions but my intuition is that this isn’t what’s going on here.

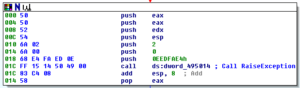

Later, after the call to 40450C, we see that something at dword 495010 is put into EDX and then EDX is TESTed to see if it contains anything – if it’s not 0, then it’s used as part of an indirect call. I couldn’t find any direct references to this double word (in terms of putting an address in there) so this is probably another thing that will have to wait until debugging. What’s interesting is that whatever is at this indirect call controls a significant portion of the remaining flow of this subroutine. If this subroutine returns 1, then the entire subroutine branches to an exit, and overall this subroutine returns 1. Otherwise, we continue to branch through these other areas related to exception handling. As part of the “failure” branch, we see a call that ultimate results in an indirect call to RaiseException:

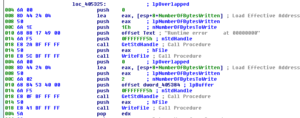

Various other calls are there, to RtlUnwind, to the unhandled exception filters, etc. Towards the end, there is a call to 407644. Several layers deep into this sub, we find some branches related to exiting the application with an error, and writing this information to a file:

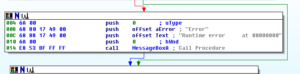

We also see that an error message can be put in a MessageBox:

Overall, we step all the way back up to where we entered these many branches, and we’re back to 48F8A0, continuing now that the malware has set up its error and exception handling mechanisms.

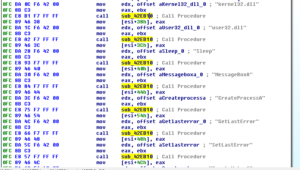

Next we see EAX being zeroed out and then some things being pushed onto the stack before a call to CoInitialize. These things being pushed don’t really mean much to the CoInitialize call, though, as this takes only a single parameter which is reserved and must be null (per MSDN: “This parameter is reserved and must be NULL”). One of the things pushed, though, was a location (490656) which contains an instruction to JMP to a subroutine at 404DE4. This appears to go down a similar rabbit hole as earlier, with similar instructions to the error handling stuff discussed above. Shortly after this, there is a call to a subroutine at 481628. This is where we appear to get into the real “malwarey” activity.

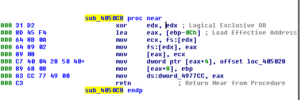

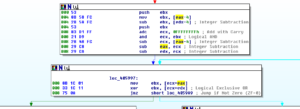

This subroutine begins with some setup and also a reference to some of the exception handling material we already saw. Next we see the value 0x320 being MOVed into EAX and then a call to a subroutine at 402F00. The first thing this subroutine does is TEST EAX, EAX and then jumps if the result is less than or equal (JLE). I must be missing something, because I would think that if you just MOVed 0x320 into EAX, then you have a JLE, you should always follow the jump – it becomes sort of an unconditional conditional (equivalent to a JMP). Here’s a quick look at this area of code:

I’m wondering if there is some sort of anti-disassembly tactic going on here. Sometimes you might see a conditional jump that appears to be “always taken”, like what I seem to observe above or something like this:

XOR EAX, EAX

TEST EAX, EAX

JZ <location>

So here we’re zeroing out EAX and then TESTing it – since we just zeroed it out, the zero flag (ZF) should be set a this point so therefore the JZ (jump if zero) should ALWAYS be followed. Sometimes malware authors can do things like this with the opcodes in order to get code to disassembly incorrectly (but still execute as intended, it’s just fooling the analyst). When I undefine this section of code and then start redefining different slices of the opcodes as code again, I don’t come across anything that appears to be meaningful, so for now I’m going to leave this be and just note that this might be someplace I need to come back to. Overall, I wouldn’t say that this is a terribly “hostile” sample, though, so I’m not as suspicious as I might be from seeing something like this.

Within this subroutine however, we eventually get sent to a somewhat mysterious, complicated and large subroutine at 401A0C. I’m not able to fully understand what this subroutine is doing – The beginning of the subroutine almost makes me think that it’s looking for an address:

I suppose this could be anything, but I feel like those values look similar to addresses. I’m not sure if this would even make sense for a sample of this age, since I think that chances are pretty slim of finding anything at a specific address in any version of Windows you might find out there for the last few years. I don’t recall when address space layout randomization first became prevalent, but I believe it was at least several years before this sample was found in the wild. The rest of this sub is full of arithmetic operations, shifts, rotations, compare/exchanges, and bitscans. At one point, this subroutine also calls another subroutine that allocates memory somewhere. Normally I would associate all of this with some sort of coding routine, but I feel that this isn’t the case here. I’m going to rename this subroutine MaybeDecoding and move on. Just in case it’s of interest, here’s a higher-level view of this subroutine, to give some idea of the activity going on here:

Coming back up to 481628, next we see calls to GetCurrentProcess and OpenProcess followed by Sleeping for 1 millisecond. One of the parameters PUSHed onto the stack is the token handle – perhaps the “coding” routine we were just discussing was some method to find an appropriate token. Perhaps the bit scanning functions had to do with that also.

Below this, we then see a call to GetTokenInformation:

I notice that number we saw earlier, 0x320, being pushed as the TokenInformationLength. Seeing this number in relation to tokens makes me think that the earlier subroutine was in fact doing something related to finding a particular token or type of token. I’m going to rename the sub accordingly.

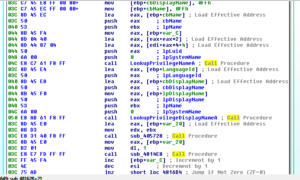

After this call to GetTokenInformation, we see additional calls to that token search subroutine, and then we see the malware looping around getting privilege names:

The subroutine at 405728 compares CL with the non-zero memory contents of four bytes beginning at [EDX]. There is a mechanism to increment EDX, but what’s interesting here is that this sub 405728 does not end with a RETN but rather with a JMP to a subroutine at 405620. This subroutine runs through some of the same code as before related to token searching / possible antidisassembly and then also calls a subroutine at 4030FC (if the token search function was successful, as an intermediate step) and 405530 (after 4030FC, or simply as the next subroutine in the event that the token search / anti-disassembly routine was unsuccessful). 4030FC conducts a number of arithmetic and floating point operations using EAX and ECX. 405530 leads us down some paths that includes code we’ve seen before, like the area that was focused on shifts/rotations/bitscanning of information. These branches within these subs lead us to more manipulations, more shifts/rotations of values, and even an exit path.

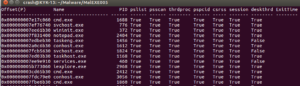

Stepping back up to 481628, the next subroutine being called is 4814E8. Within this subroutine, we see the process token being opened, and also some error handling functions. What’s very interesting is that later on in the code, we see the privileges of a token being adjusted in order to remove all privileges:

I wonder if this is some scheme to hide activity from the user. I’ve read about techniques involving replacing user privileges with administrator privileges so that the malware can more stealthily conduct activity that normally would appear in Event Viewer. This is going to be my working model for this, at least for now, as I haven’t really heard of malware that “de-escalates” privileges. After some more calls to the manipulations code we’ve already seen, sub 481628 finishes and we’re back up top at the Start function.

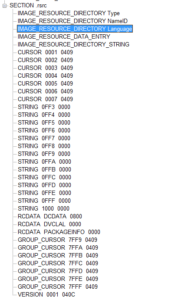

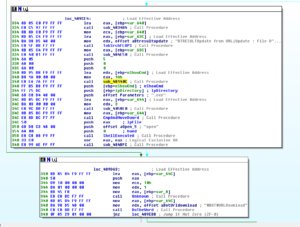

The next subroutine, 48DECC, conducts more transformations of data and floating point operations. 48DF40 is the next subroutine called, and we see “DCDATA” being MOVed into EDX shortly before this call, as well as having its own exception handling being set up right before that. The major things that 48DF40 do include:

– Sub 48DDC0 which involves finding/loading/locking/freeing the .rsrc section, as well as some of the previously seen floating point operations and token activity

– Sub 405864 which involves more of the same token activity and floating point operations

The next sub, 48DF40, contains many, many manipulations and floating point operations, as well as a possible exit path. I’m not interested in digging through what all of these are doing, as I want to keep moving on to what I consider to be the main malware operations. After that, sub 40F21C calls GetModuleFileNameA and also one of the manipulations subs from earlier. Next, 40A588 was not obviously interesting, though right after that we see an offset for “GENCODE” MOVed into EAX and then a call to 47DFE4.

Digging into the subroutine at 47DFE4, I continue to get bogged down in what appear to be endless manipulations of various registers and floating point operations. I’m not really trying to reverse this sample in the sense that I want to understand exactly how it works (how it is written / could be rewritten) but rather I want to disassemble it in order to try to glean the interesting parts of the malware functionality. It’s a good exercise in any event, as this is the largest sample I’ve ever tackled, but I think I’m going to change my tactics on this. I’m going to start looking at specific functions and strings of interest and then work around those in order to try to get to the interesting stuff faster.

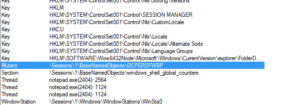

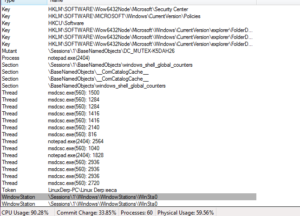

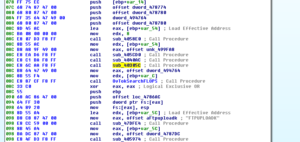

Going in no particular order, I’m going to take a look at mutex creation in this malware. We saw earlier that a mutex DCPERSFWBP was created. This string appears in the malware and is referenced in a subroutine at 42F27C, which turns out to be a very interesting subroutine. We see some manipulations and floating point operations being done, and then we see some of these being done in the context of notepad.exe:

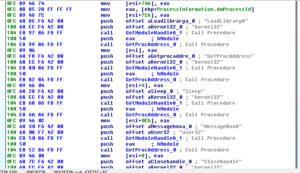

The first reference we see to DCPERSFWBP follows this, right before a call to CreateProcessA:

After that, we see something odd:

We have a series of strings being used in conjunction with a call to a subroutine at 42EB10. This subroutine consists mainly of calls to an earlier privilege name searching subroutine, and then a call to VirtualAllocEx and WriteProcessMemory.

After that, we see calls to GetModuleHandle and GetProcAddress:

This looks familiar and strange at the same time. This looks like the malware is getting a handle to a module and then calling GetProcAddress in order to get the address of a function to import. Maybe this is something to do with how Delphi handles this sort of task. I’m more used to seeing the LoadLibraryA/GetProcAddress combination.

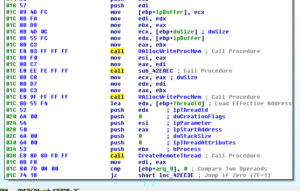

Towards the end of this block of code is a call to a subroutine at 42EBD8. The main things happening in this thread are a couple of calls to subroutines that call VirtualAlloc and WriteProcessMemory, then a call to CreateRemoteThread:

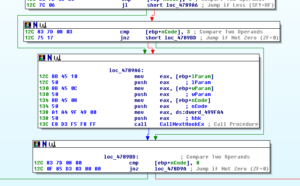

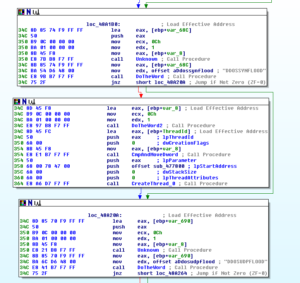

Another aspect of this malware that’s interesting to me is the surveillance capabilities, such as the keylogging and webcam functionality. There are some strings that lead me to these places, such as CTRLA and WEBCAMLIVE. I notice that there seems to be a common subroutine found whenever named functionality appears to be called – see a couple of screen shots below:

As you can see, the offset for WEBCAMLIVE is MOVed into EDX right before 405974 is called. This code comes from an absolutely monumental subroutine beginning at 4850A8.

Here we see this same subroutine being called, this time in the context of recording CTRL key combinations in the keylogger. This code comes from a subroutine beginning at 481A6C.

405974 is interesting because there doesn’t appear to be an obvious call to something that would cause the action to take place. 405974 begins with a few comparisons and tests:

As you can see, there is a comparison of two registers (EAX and EDX) and then a TEST between the same two (though in different order). What we’re missing from this view is that prior to 405974 being called, a parameter is put in EAX while EDX receives an offset pointing to the action – here’s a view of this coming from 4850A8:

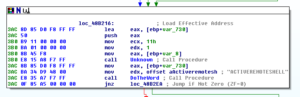

Going back to 405974 now, we:

– compare the two – if equal (zero), we jump to a RETN

– test the two – again, if equal (zero) we jump to another test

– at this second test, we test to see if EAX is zero – and if so, jump to a couple lines of code where we compare the variable 4 bytes behind the current offset in EDX to what is in EAX, and then RETN

– if EAX is nonzero, then we test EDX to see if it’s nonzero (see below for more code), continuing with the code if it ISN’T zero (at which point, we execute a couple of lines to do a similar comparison of what lies in memory at EAX-4 bytes with EDX)

– If we get through all of that, then we MOVe with zero extend what is in memory at the location specified at EAX into ECX, then subtract the lower byte of ECX from the contents of EDX, jumping to a RETN if this results in a nonzero result

– Next (see following image), assuming we didn’t jump to the RETN, we can see some manipulations taking place – contents of EBX get saved by PUSHing them onto the stack, then we see the contents of memory at EAX-4 bytes being MOVed into EBX. The contents of EDX-4 bytes are subtracted from EBX, then we get this new result PUSHed onto the stack also. What’s in ECX (which, remember, contained the contents of memory at EAX-4 bytes with the contents of EDX subtracted from the low byte at CL) has 0xFFFFFFFF added (with carry) to it. The result of this will be to take the contents of ECX, add 0xFFFFFFFF and the result of the carry to ECX. ECX and EBX get ANDed and then we see the contents of memory at EAX-4 bytes being subtracted from ECX, then ECX being subtracted from EAX, and then finally ECX being subtracted from EDX. Some sort of decoding?

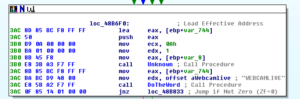

– In the next block of code, the contents of the memory stored at the address resulting from the sum of ECX and EAX are MOVed into EBX. This then is XORed with the contents of memory located at the address resulting from the sum of ECX and EDX. This block finishes with a Jump if the zero flag is set.

– If the jump is not taken, then we ADD 4 to ECX and loop (via the JS) if the sign flag gets set, otherwise we follow a branch where we POP EAX, add EAX to itself, and the POP EBX before continuing to the RETN. Stepping back through the code, the contents of EAX should be the last thing PUSHed onto the stack (which was the contents of EBX, which had the contents of EAX-4 bytes MOVed into it before having the contents of EDX-4 bytes subtracted from it) and the contents of EBX should be the next thing on the stack, which in this case would be the returned value from a successful call to recv in the WS2_32 library. In order to find this, I had to move up several levels in the code, and will put another screenshot below showing this.

Screenshot showing the contents of EBX, code copied from subroutine 479E38:

Coming back to 405974 now – there’s a final branch to look at, see below:

– Once the loop is finished (and the JNZ is taken), then we enter a block where we bitscan forward (BSF) EBX with itself, and then shift the result to the right by three places. This new value in EBX gets added to ECX, and then we come to another conditional jump. If the jump IS taken (sign flag did NOT get set) then we head over to that branch already discussed where we have values being POPped into EAX and EBX. Otherwise, we go to the last block of code to look at in this section.

– If the sign flag does get set, then we move the contents of ECX+EAX into AL, compare AL with the contents of ECX+EDX, and then POP the last two values on the stack into EBX before returning, which in the process loses the first value that was left on there (which was the contents of EBX, which had the contents of EAX-4 bytes MOVed into it before having the contents of EDX-4 bytes subtracted from it) and leaving only the second thing PUSHed onto the stack in EBX (the returned value from a successful call to recv in the WS2_32 library, after the BSF and SHR have been executed on that value).

– Finally, keep in mind that the discussion of what is in EBX here is going to be dependent on exactly where this subroutine is called – in the example I gave above, this particular instance of using the code had to do with values returned from the call to recv, but this sub 405974 is called 357 times in the malware so obviously the values of the registers can vary widely from call to call.

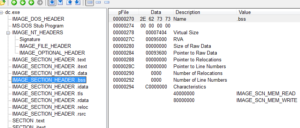

So what does this entire mess actually mean? To be honest, I’m not entirely sure. Overall, we have an action being taken depending on whether or not a parameter being passed to the function matches a string stored at an offset. I’ve observed MANY different situations and offsets in this code. At first glance it’s almost as if the malware has a parameter passed to the function and then it checks against several different command names within that function. It sort of appears to be an inefficient way of doing this, since in some cases you almost cascade through a large number of code blocks checking along the way. It also looks like this is some sort of way to decode an address within the malware execution. There’s a .reloc table within the PE header, perhaps this is some way of finding functions within the code if the malware is able to ascertain where parts of itself have been relocated? I think I need to look at more samples of malware written in Delphi so that I could get a better idea of what is happening. Coming from a background of looking at samples written in other languages, this code doesn’t appear to really “do” anything so I suspect that this is just my lack of knowledge of Delphi showing through. At least you got treated to an excruciating walk through of some assembly code!

Moving on to other malware functionality, going through the functions imported in IDA I notice that there’s a subroutine beginning at 478968 that contains a call to CallNextHookEx. The malware could hook things for various reasons, but in checking this subroutine out we see that it begins with some code that includes the call to CallNextHookEx, and then a check is done to make sure that the hook code passed is nonzero:

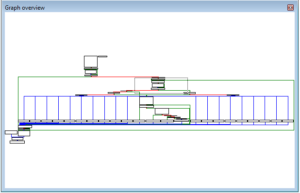

If it is nonzero, then we jump to a code section built around another call to CallNextHookEx, before doing some cleanup and returning. Otherwise, the code continues to an area containing a couple of large switch statements (overall a couple dozen cases, see graph below):

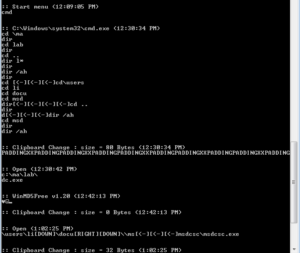

Within here, we see code that calls GetKeyState and also branches that will allow the malware to add other information to the log file, such as the code that adds in statements about the clipboard status and other things:

Here’s an example of one of the subordinate subroutines showing a reference to text that gets added to the log file for clarity:

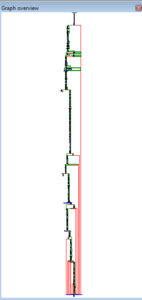

I went looking for a reference to UrlDownloadToFileA and found one in the giant subroutine 4850A8. Here’s a graph of that subroutine to give you some idea of the scale:

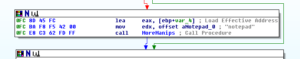

Somewhere very close to the bottom one finds a reference to UrlDownloadToFileA. It’s not clear from the disassembly precisely what file is being downloaded, however we can see later that if the file is successfully downloaded that this status update is reported and also this file is executed after downloading:

We can also see the reference to Bots here, suggesting this is part of the functionality offered via this malware. What I’ve also noticed in browsing through this very large sub is that there appears to be another subroutine that is similar in its role in the malware to 405974. You might recall that 405974 was the subroutine taken apart in some detail earlier, and this was one of the subroutines that would “do” whatever was being referred to in the malware according to a particular string. I’m noticing that this new subroutine at 405A84 also appears to fulfill a role like this (and happens to be referenced 296 times, a similar volume compared with 405974). I’m not going to go into the same amount of detail in looking at 405A84, but this new one seems simpler while also have some resemblance to 405974.

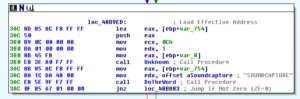

Further along in 4850A8, we see references to some of the bot-type functionality related to floods:

Here’s a reference to remote shells:

References to using the webcam and capturing audio:

There are many other references that suggest additional functionality such as getting torrents, sharing the host desktop, getting the victim’s clipboard contents, playing sounds, opening and closing the CDROM drive, opening Task Manager, and other things.

Here’s a little thing I noticed going through other areas of the code:

I’ll keep this in mind for the signatures part of this analysis.

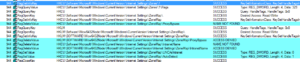

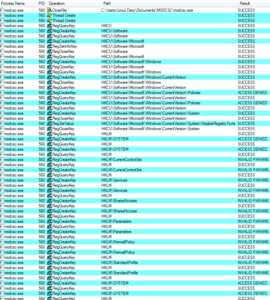

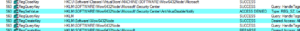

471E70 is where we see references to several registry changes, including ones related to persistence:

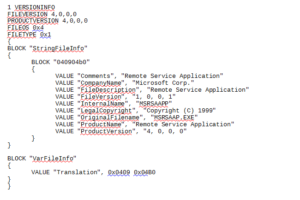

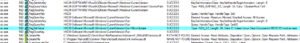

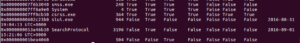

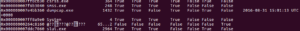

In the subroutine at 483A04, the malware obtains and names the version of Windows it is running on:

For some reason, the only version it explicitly names is Windows Server 2003 (in terms of referencing a string):

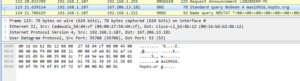

I’m getting to the point where I need to move on from this sample, so let’s take a look at some of the stuff I dumped using Volatility. Starting with the second of the two iexpore.exe processes, there was code injected at two places. Looking at what I dumped from the first place (at 0x420000), I see what appears to be several hundred lines of a sled that all lead to a jump to 0x76AD9204, example below:

I tried attaching a debugger to this process to see what was at this location, but none of them allowed me to (all of my versions of Olly and Immunity). The other dump from this same process, at location 0x5FFF0000, didn’t make any sense, so I’m not sure what this is.

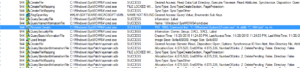

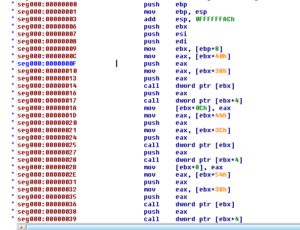

Looking in the dumps from the notepad.exe process, two of the dumps contain code that I can’t make sense of (I wouldn’t call them spurious just because I don’t understand them…) but one of the injected areas does appear to contain code with many indirect function calls (found at 0x1A0000):

I’m wrapping up this analysis at this point, as think I’ve gotten as many interesting things as possible out of this, particularly during the dynamic analysis in the previous post. I could spend a lot more time on this sample, and maybe down the road I should so I can get a better handle on Delphi. There are a few more things I’d look at if I had more time:

– Figure out what is preventing me from attaching to one of the injected iexplore.exe processes and further investigate the address I found in the injected code. One other thing of note related to this, is that while there is a TLS section (which as far as I know is normally associated with antidebugging techniques), IDA does not see an entry point associated with it.

– How the domain name is generated within the code, as I did not see any string looking like “max19916.hopto.org”

– The log file generation code (it appears to be pretty simple, but I would still be interested in seeing the specific code that does this)

– Where the code actually specifies the msdcsc.exe file name (again, I did not see a direct reference to this in the disassembly, nor for the directory name generation)

– Mutex name generation (we saw that there is a static piece that we did find, but there is also a dynamically generated piece)

References:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/.bss

Findings and observations:

Remote access trojan coded in Delphi. Extensive functionality to monitor user activity (inputs, files, desktops, remote shells, audio/video equipment). This malware also appears to have capabilities more often related to botnets (such as DDoS capabilities).

Recommendations:

Avoid downloading files hosted publicly on DC hubs (or other P2P services). Don’t allow users access to these services without some vetting (e.g., an IT professional may need access to bittorrent in order to obtain Linux ISOs). Keep regular users from running in administrator mode, as there was a bit of lost functionality for the malware in terms of system control when run as a regular user. Blocking the domain max19916.hopto.org would be good, but given the number of shady sites hosted at hopto.org it might be best to simply block the entire domain.

Conclusion:

A very interesting sample, particularly around how it was being distributed. The extent to which one could invade a victim’s privacy with this malware was a bit disturbing.

Report:malexe005

Hashes:

MD5:be1fa25529308e909381777bcd7f0e92a

SHA1:9a3c2eefb12d527d2d7377a8c6f96854baf566c9

SHA256:d673493ef6288338bace20a165b32b7fb897400e943c7b313a0cef3d1cba22dd

ssdeep:12288:C9HMeUmcufrvA3kb445UEJ2jsWiD4EvFuu4cNgZhCiZKD/XdyF5:uiBIGkbxqEcjsWiDxguehC2SE